In 1993, when I was 23 years old, I left my suburban Vancouver home with nothing but a backpack, a lonely planet guidebook, and a surfboard. 48 hours later I found myself standing on a street corner in Jakarta with my gear at my feet, and for the first time in my life I thought I understood what Heidegger meant when he talked about experiencing the nothing. Alone, in my complete estrangement and isolation from all things that I had known, I literally felt the totality of everything retreating away from me. It was a transcendent moment to be so alone with myself, and for the next 3 years, as I traveled the world and lived immersed in cultures so foreign to my experience, I often returned to that moment of isolation where alone I was also never so aware of my own unique self in the world.

So was the general theme to my travels – I was the classic thinker – (over thinker) engaged in a pursuit of experience and learning, all the while believing I was its master. Traveling up my own metaphorical river, the trip grew hotter, the jungles deeper and more tangled, and the current more arduous to traverse. And that clearing from which I experienced being began to close in, and instead of the retreat of the nothing I felt what I called the encroachment. I felt everything. It was a completely self-indulgent exercise where I embodied the weight of everything and everybody. I took on their joys and sorrows, unable to detach from them – embracing their sins, burdens, and pains – sometimes laughing , sometimes crying. It was intoxicating as I cloaked myself in the robes of the martyr. I was young and I thought I could handle it – but equally I was not alone. The weight itself was enormous and its density had a gravity that attracted other like-minded souls. And that’s the state I found myself in, when almost a year later, I was living on an isolated beach in Thailand, in a small community of lost and weary souls, our hearts bleeding for the world.

Ko Pha Ngan is a legendary place in backpacker lore, and everything you’ve heard about it is probably true, and then some, in term of its excesses. But in the late eighties and early 90’s there were still parts of the island that were completely isolated from the rest – cut off from the madness of Haad Rin and its full moon, techno and trance fueled parties. And in these places, remote and isolated, some without roads-in even, communities of travelers formed. And so we were – a collection of travelers, each suffering some existential heartbreak that we’d all turned into a fetish.

There was no world wide web (not really) and no cell phones, so contact with the outside was limited to letters home and brief telephone calls at various ports of call. In those days, when you left home to travel in places like South-East Asia, you left behind your connection to family and friends, media and world news, and above all – pop culture. Forget CNN, or MTV. There was no email to speak of, or Facebook – no status updates or text messages. You were cut off from it all. Your favorite band could have a new album out and you’d have no idea. This was the nature of travel in the waning years of the disconnected age. And music – often the lifeblood of young people – was a precious commodity.

If you were lucky you had a few cassettes. They were either mixed tapes or full albums that had been acquired on the road or brought from home . And they served as a special kind of shorthand — a way of saying “this is me” without the complexities of language and culture to get in the way. And as groups of travelers got together and formed communities and bonds, no matter how brief, there emerged a soundtrack from the collective that defined the moment that came from these shared cassettes. And sometimes a traveler would arrive with something entirely new and unexpected – something unknown that was not yet part of anyone’s musical history or identity. Sometimes a piece of music would so emotionally resonate with us and the now that we’d weep for joy in our shared discovery, embracing each other as initiates,. It could be Swedes, Germans, Australians, Brits, Canadians, and Americans – all coming together in a single moment of discovery on a beach somewhere when a new piece of music was experienced collectively and embraced by the group. It was in a situation like this that I first heard the album Shame by Brad.

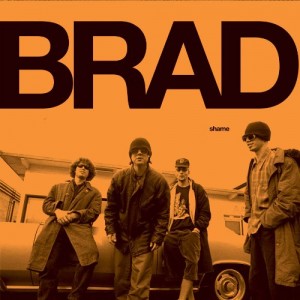

It is now 20 years later and that album and my experiences with it are still as precious to me as they were all those years ago on the beach. In celebration of that moment from my past, but also to coincide with the album’s re-release on the Razor & Tie label, I feel compelled to share a few more words about it in the hopes that others will discover something for themselves by checking it out. It is truly one of the best albums of the 90’s. And the good news is that Brad is by no means a dead project or band – they are still actively touring and recording together. In all these years I’ve yet to catch them live though there was a time when I unknowingly found myself at a Shawn Smith solo show where some Brad material was played that nearly knocked me off my feet (another story for another article).

Brad: The Band As It Was On Shame

Brad is a band of timbre and textures, of haunting melodies and suspended chords crying out for resolutions – of sweet gentle sorrow, and graceful melancholy leading into rivers of sublime joyousness. Rarely has music been so effectively expressionistic – not in the abstract, but in the existenz, capturing human emotion as a layered polyphony. Sad and happy exist simultaneously with equal parts exaltation and lament – and it is this quality that haunts one’s memory of lives and loves past, like a delicious bite, and the last twist of a knife.

And this owes to some unique talents in the band members, who in their instrumentation, weave these wonderful tapestries through songs that seem to have materialized directly from emotional experience. It’s a rare thing to have an album of songs be so well supported by a band where the songs themselves and the emotional experience of them are the primary takeaways after listening.

Top of these is Shawn Smith – impresario and wordsmith whose voice and piano comprise the main melodic instrumentation within the songs. Shawn’s voice has a smooth rasp – the texture of finely brushed copper or brass that dissolves into infinity. It’s white soul without the pretty eyes – his pain worn weighted on the body. Shawn’s vocal personae is equal parts yin & yang. It can still be uplifting or upbeat, but its always bathed in naked emotion; vulnerable and honest even in its deceit. He creates tension in his vocals through the selective use of tritones, leaving vocal lines and cadences unresolved – or with the resolution only suggested by the vacuum. The melodies themselves are given momentum and supported by fairly restrained syncopated piano comping, and they flow through the body of the songs like a river over land. To follow the melody is to follow the path of the river and the destination is wherever the river takes you. Each listen of each song can take you to a different place. In this way the narrative form of the lyrics and melody is liminal, not literal. It makes for amazing flights of the mind for the listener.

On drums is Regan Hagar – who approaches the music with a clean percussive jazz style. Reminding me a little of John Densmore, Hagar is great at leaving space between notes, and using textured strokes and beats to add more timbre to the soundscape. This may be a function of his overall style or simply how the band knits together – either way his use of restraint, and the respect for his bandmates (who each provide a very rhythmic contribution to the songs through their own instruments) shows a drummer with a real maturity and confidence who knows how drums can fit instrumentally in the whole of a song’s arrangement – not just on a singular rhythmic plain. This totally adds dimensionality to how the band breaths.

The bass is phenomenal on Shame. Bassist Jeremy Toback is a singer songwriter in his own right and his parts are composed and played with the sensibility of a songwriter. At its heart is a very round and smooth Motown style of moving lines and counter-melodies, punctuated with a restrained funk. There’s some counterpoint, lots of melody and syncopation, and the bass often leads or anticipates the changes and/or closes the suspensions left open by the piano. Like the drums (and guitar) this really gives the songs an incredible depth, but leaves lots of space within the soundscape for the songs to breath. Although there are funk sensibilities within the playing it’s not is funk to be funk (which totally makes it stand apart the early 90’s contrivances of the funk rock movement). If you took James Jamerson and added a dash of Eric A and a whole lot of Paul McCartney you’d have Jeremy Toback and his bass on these albums. It’s high praise, but this is a unique band and Shame is a unique album. There are a few bass moves here that are a real joy to discover. Try listening to this album focusing solely on the bass – when you do this you’ll hear what I’m talking about. It’s an amazing bass masterclass for any student of the instrument.

Like the drums and bass, the guitar here is played with such economy, but with such purpose that the economy isn’t obvious. Colour is painted in very broad brushstrokes. Stone (Goassard, of Pearl Jam) is a master at this kind of compositional focused playing. He gives great texture to songs without drawing focus to the guitar as a lead instrument. At times his playing takes the role of a horn section in a good jazz combo – playing lines and motifs in parallel or contrast to the melody. Sometimes he’s just adding richness like a good alto sax part. Sonically this leaves lots of room for the piano and Shawn’s vocals, and again the economy creates lots of liminal space. His voicings are always really interesting – perfectly complimentary – and they absolutely haunt the songs providing an almost an ethereal layer of sonic liquidity. Another masterclass for sure. And don’t forget about the heavy grooves. Stone can bring on the groove just when you want to hear it, and he can run with it as far as you want to go as well.

My original intention was to do a song by song analysis of Shame but I don’t think that’s the way to go at this point. As far as reviews or articles go this one’s already unconventional – lots of personal stuff (with some over-the-top sentimentality and self indulgent recollections) – to then burden you with my take on every song would be the worst thing I could do. All I will say is that this is a great album to put on with the lights dimmed, with maybe some candles burning (for the smell of paraffin as much as the light) and some time set aside to truly experience the music – start to finish. A bottle of wine works too if you got that — sip the wine and let it warm you while the album plays. I guarantee you’ll find moments on the album that you’ll really respond to and I hope the experience is as rewarding to you as it has been for me. If you’ve gotten this far in the article I thank you for wading through the crap to get to the treasure – for that is what the album is to me – a real treasure. Regards.

R.

Title Photo Credit: Sachyn Mital, Under CC by SA 3.0 Source