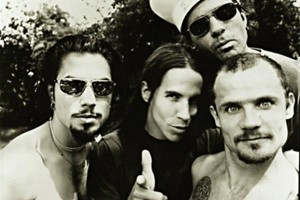

In 1995 the Red Hot Chili Peppers released One Hot Minute – a follow-up to their multi-platinum 1991 release Blood Sugar Sex Magik. BSSM had catapulted the ‘Chilies’ into the mainstream, rising from obscurity as an LA based proto-punk-funk-ska outfit to the top of the world album and video music charts. Recorded over several years, with no small degree of dysfunction and disharmony One Hot Minute is a masterful release unto itself that should be considered an existential tour de force with the band weaving sonic tapestries of mood and timbre previously unachieved as the bedrock for what was singer Anthony Kiedis‘ most personal and mature lyrical contribution to date.

In 1995 the Red Hot Chili Peppers released One Hot Minute – a follow-up to their multi-platinum 1991 release Blood Sugar Sex Magik. BSSM had catapulted the ‘Chilies’ into the mainstream, rising from obscurity as an LA based proto-punk-funk-ska outfit to the top of the world album and video music charts. Recorded over several years, with no small degree of dysfunction and disharmony One Hot Minute is a masterful release unto itself that should be considered an existential tour de force with the band weaving sonic tapestries of mood and timbre previously unachieved as the bedrock for what was singer Anthony Kiedis‘ most personal and mature lyrical contribution to date.

The RHCP’s were an obscure and somewhat annoying band when I first made their acquaintance during 1986’s Expo 86 in Vancouver, but their infectious enthusiasm for mischief and their self confidence absolutely sold me on them as someone to keep an eye on. Their first two albums had been frantic affairs with a very brittle production and sound. The performances were particularly abrasive and challenging to the listener much in the same way the Ramones performances were – almost like a dare to see if you could continue listening. Those that did were rewarded with 1987’s Uplift Mofo Party Plan, with songs like Funky Crime, and Behind the Sun finally showing a more cohesive conceptual musical direction for the band. The proto-punk-funk-ska 4-some had added some Hendrix to the mix, and Keidis had finally discovered the power of melody. There was still a brittle edge to the mix but the groundwork was solid on which to build – the next album was promising to be epic. Tragedy then struck the band with the sudden loss of guitarist Hillel Slovak to heroin. Amazingly the band continued on with a new release – 1989’s Mother’s Milk – and a brand new guitarist, 18 year old John Frusciante.

Mother’s Milk fully embraced melody and featured a more mature & refined song-craft from the band with both personal and universal themes. Frusciante proved to be a monster of a player and his live performances of that tour were a showcase of his youthful bravado and enthusiasm for having found himself at the guitar helm of his favorite band, and a near preternatural ability with a Stratocaster. Always speaking to the disenfranchised, with Mother’s Milk the ‘Chilies’ found the audience primed and ready to listen, and the band united with them in grief. By the time Blood Sugar Sex Magik was recorded and released that audience had grown as part of the “Alternative Nation” (that had been birthed and united ironically by the band Jane’s Addiction before their eventual implosion in 1991) and with mainstream crossover proved enough to crown them the New Kings. The BSSM tour was legendary and I was privileged to see 3 shows at 3 different points in the tour. Each show was dynamic and brilliant (and different) but it became increasingly clear to me was that something was seriously wrong with Frusciante. You could see him withering and withdrawing over time from the band, the audience, and reality in general as the tour progressed. His near total personal collapse into a drug psychosis shocked no one and he exited the band on his way to what we all thought would be an early gr ave.

ave.

After Frusciante’s departure and the success that was BSSM, the RHCP’s suffered through a couple of short lived replacement guitar players before bunkering down with former Jane’s Addiction guitarist Dave Navarro to record One Hot Minute. Far from an easy recording process, the musicians in the band worked for several years on the music with long stretches of inactivity while Anthony struggled with his own drug relapses and a general frustration at how difficult and different the writing and recording process was from their previous efforts. The irony in this is that One Hot Minute features perhaps Anthony’s deepest and most personal lyrical journey on record. Gone is the fictional personae Anthony wore as a mask in previous song constructs, and absent too are the long steam of consciousness free-form raps that characterized many of his earlier vocal efforts. It’s precisely this, facilitated by the more sonically impressionistic brush strokes of colour and darker edge that Navarro brought to the process, and the restraint shown by the rest of the band (particularly bassist Flea who both stepped up here and back) that make this album great unto itself.

It’s a mistake to look at this album as any sort of linear point on a musical timeline — it’s much much bigger than that. Take the cue from the aptly named song “Walkabout” — this album is a spiritual journey that transcends any notion of linear time and narrative — it’s an experiential album — an existential expression and affirmation of precisely what it means to be alive. It deserves to be listened to in the way you might sit down with classical music and if it’s not queued up on your iPod – go get it – and find a quiet space in which you can close your eyes and sit back and listen to it through and through. Doing this with the lyrics in your hand is particularly rewarding.

It’s no wonder that both the band and fans have found this album difficult to reconcile into the catalog. After climbing the highest peaks of success with BSSM and inexplicably losing Frusciante and later themselves in what should have been a time of great celebration, the RHCP’s produced an album that was deeply personal and deeply painful – with their existential struggles laid bare before an audience that still wanted to celebrate. I see this almost like a birth trauma (or a rebirth trauma) for the band and the music and lyrics perfectly capture the pain of standing before the mirror and finding it all in question and going to shit when you thought you’d already transcended that. In this way the album is a casualty of precisely the thing that makes it a brilliant piece of art. It serves as a twist of the knife – and some memories we don’t like to revisit.